China Price Index: Establishing an ‘Ecology of Ag Innovation’ Is Key to China’s Supply Chain Success

Editor’s note: Contributing writer David Li offers a snapshot of current price trends for key herbicides, fungicides, and insecticides in the Chinese agrochemical market in his monthly China Price Index. Below he also projects what the future of competition will look like for the crop protection market and how companies that establish an “Ecology of Ag Innovation” will become more sustainable.

On June 17, 2024, Nutrien Ag Solutions completed the acquisition of new biocontrol technology, which is a chlorin-based photosensitizer, to the global market as a novel solution for integrated pest management (IPM). According to the press release, the acquisition is aligned with Nutrien Ag Solutions’ strategy to invest in novel, patented, and effective biocontrol technologies through its Loveland Products business. Biological ag inputs seem to remain hot for multinational agricultural distribution companies. This is apparently due to the higher growth rate of biologics in the global agricultural market in recent years.

Not only agricultural distributors keep a high interest in biological technology, but also multinational companies demand the possibility of acquiring more biologicals in the local market. On May 29, 2024, BASF China’s Agricultural Solutions Business Unit signed a strategic cooperation agreement with Anhui Huaheng Biologicals, whereby both parties would deepen their strategic cooperation in the field of plant nutrition. The main mode of cooperation is to support the product development of biostimulant through the establishment of a joint R&D laboratory.

Huaheng Bio is favored by BASF mainly because Huaheng Bio itself is one of the suppliers of BASF. Huaheng Bio’s core business is synthetic biotechnology, and its main products involve amino acids and derivatives. Among them, alanine series products are the main source of revenue for Huaheng Bio. As multinational companies operate with a greater focus on managing existing product assets, introducing external innovations is gradually becoming a major way for companies to explore growth margins in the market.

This trend has in fact continued for about 20 years. There are two main models in the global innovation ecosystem: one is the innovative R&D model dominated by North American venture capitals. In North America, investments in agriculture are more private equity oriented. Agricultural investors and investment funds hire former executives of multinational agricultural companies as investment advisors. These former executives who used to work for multinational companies are very familiar with the R&D pipeline of multinational companies.

At the same time, they also understand the market demand very well. More importantly, they clearly understand the gap between the MNC’s R&D pipeline and the market demand. Therefore, they will guide entrepreneurs in the agriculture sector to choose the right direction of R&D. In the field of investment, the most important thing is the exit mechanism of capital. These innovative companies born in incubators from North America are more inclined to be acquired by multinational companies. The innovations they develop can be merged into the product line of the multinational company in parallel. Thus, the entrepreneurs can get an excess return on their investment in the shortest possible time. This also gives serial entrepreneurs the opportunity to continue to invest in R&D and reap the benefits.

The second is the model used by Chinese entrepreneurs. Across the ocean in China, the innovation path is very different from North America. Chinese innovators are more inclined to develop disruptive technologies. They raise capital on top of technological innovation. With venture capital, they utilize the funds at hand to conduct vertical R&D for different industries. Chinese innovators usually use their R&D results to gain access to core customers and eventually run their companies to stock market. It can be said that the direction of Chinese innovation has evolved into two parallel lines with the direction of overseas R&D.

Overseas innovation model is oriented to customer and market demand. While China’s innovation model is based on technology iteration as the basic starting point. There is no absolute right or wrong between these two approaches. The overseas model can get a quick return on investment. The latter prefers to build leading companies with iterative technology in the industry, thus taking the initiative in the future “blue ocean” market. One is a short-term strategy, while the second is a more long-term sustainable strategy. Regardless of the strategy, it is the right one if it yields the reasonable returns that shareholders and investments expect.

This shift also raises a new question for globalized companies: how to maintain a focus on two parallel lines of innovation at the same time?

R&D Collaboration with China in Progress

Among the four major multinationals, Syngenta is a leader in R&D cooperation. Over the past decade, Syngenta has been committed to collaborating with various R&D organizations in China. They maintain sensitivity to China’s R&D progress by establishing R&D programs with Chinese research institutes and various universities. Syngenta’s strategy is clearly more pragmatic. They use their channel strengths to introduce convincing R&D results that have been proven in field trials. However, due to Syngenta’s own financial pressures, Syngenta’s venture capital investment in Chinese innovation is relatively scarce. Syngenta’s partnership priorities with Sinochem are also a constraint on the company’s investment on other Chinese crop protection innovation.

Bayer CropScience’s relationship with China has lagged behind, possibly because of Bayer’s increased focus on its seed business and its response to farmers’ lawsuits against glyphosate issue in North America. But more central to the resistance is the lack of an R&D decentralization strategy at Bayer. It wants to have a firmer grip on control. But in a world of global R&D and global competition, that strategy seems a bit out of place.

Of course, Bayer is also actively seeking breakthroughs, such as Bayer’s Leap team, which focuses more on early-stage innovations and invests in them. This strategy has its advantages, which can lock the product IP in advance and get the maximum return on investment with the least effort. However, for cooperation with Chinese R&D companies, Bayer’s team may need to enhance its permeability. This is because Chinese R&D and innovation is mostly pragmatic. The early stages of R&D in China may be hidden in specialized technology innovation companies and university R&D teams. Iterations of disruptive technologies need to be corroborated by the market. And once the technology matures, the company’s valuation will increase accordingly. In this case, it is critical to balance the need to acquire disruptive technologies while controlling the cost of paying for them.

Corteva’s cooperation with Chinese R&D is at an early stage. Corteva would be more focused on gaining supply advantages in China than R&D. They have previously co-financed a joint venture with Lier Chemical in Guang’an. The main purpose of that investment was to help Corteva gain access to the advantages of China’s upstream raw materials. And moreover, Corteva is also focusing on 3rd party alliance by license-in strategy. They are far from being in a position to build their own ecosystem in China.

BASF is more interested in the introduction of end-products and the expansion of field application technologies. They are more concerned with filling in the gaps in their own portfolios. This can be seen in BASF’s cooperation with Huaheng Biologicals.

“Local R&D + Local Promotion”

The pattern of access to innovation by international crop protection companies is shifting at an accelerated pace. The shift from “global R&D + local promotion” to “local R&D + local promotion” is accelerating. In the target market, R&D teams can more directly grasp the changes in market demand and adjust their portfolios. According to the recruitment information of BASF Shanghai, BASF is actively laying out the construction of R&D center in Shanghai, and the main target is the fast-growing UAV plant protection market in China.

However, as multinational companies are important to protect existing product assets and manage product categories. Expansion of local product brands can be challenged by supply chain and sourcing strategies. As a result, some companies are cautious about introducing external R&D. It is difficult for management to delegate the management of product assets as well. This is not an easy decision for any multinational company. However, the Chinese market is one of the most competitive single markets in the world, and it can influence the growth of market value across the Asia-Pacific region by supply from China. For example, drone crop protection is growing at a rapid pace in the ASEAN region, so building on China’s R&D and taking advantage of the cost as well as productivity advantages of China’s AI and formulation industry chains may become one of the options for globalized crop protection companies in the future.

The Dilemma of China R&D

Of course, there are two sides to everything. Chinese R&D innovation has its own problems. Since more Chinese innovation is concentrated in universities, how to commercialize innovative technologies is a key issue for Chinese R&D teams. Chinese R&D specialists have a very low level of knowledge about business collaboration. This is the reason why many product development and marketing efforts based on universities and R&D institutions have failed. We can’t expect university professors and PhDs to be as good at research as Steve Jobs and Jen-Hsun Huang. But Chinese researchers still have a lot of lessons to learn about weighing the pros and cons and accepting reasonable business terms. We have to admit that there is a huge barrier between the results of Chinese research institutions and successful disruptive products for the market.

However, we have also seen some positive cases. For example, Jiangshan is collaborating with Syngenta to develop the patented compound JS-T205, which was developed by Shenyang Sinochem Agrochemicals R&D using saflufenacil as a lead compound combined with an isoxazoline functional group. It is developed by intermediate derivatization method. JS-T205 is a new type of uracil-structured PPO-inhibitor herbicide with the biological properties of both uracil and isoxazoline functional groups. JS-T205 has broadleaf weed control activity close to that of saflufenacil, as well as excellent grass weed control activity.

In 2018, Syngenta conducted a field trial in the U.S., and the results of the field trial showed that JS-T205 compound was more effective than glufosinate, saflufenacil, carfentrazone-ethyl, and flumioxazin, and especially had excellent weed control effect on grass weeds.

JS-T205 is now one of Jiangshan’s strategic products and Jiangshan is investing 2 billion CNY in 2022 in Yichang, Hubei Province, to build a production facility for this product. The total future production capacity of the product will be 2,000 Mt/a, with 500 Mt/a in Phase I, 1,000 Mt/a in Phase II, and 500 Mt/a in Phase III. Jiangshan expects the product to be available for the market launch in 2024.

Syngenta and Jiangshan are jointly developing the global market. For JS-T205, the non-selective herbicide market is the preferred beachhead market. Due to its soil activity, it will also be expanded to field crops in the future, with pre-seedling treatments. With technical support from Syngenta, JS-T205 would also be used in programs for genetically modified crops.

Thanks to the participation and investment of Chinese manufacturers and the support of multinational companies’ global promotion channels, the products of compounds discovered in Chinese research institutions have the potential to be truly introduced to the international market. Regardless of the outcome, it’s exciting to see patent compounds discovered in China can enter into the world from China.

We have seen a number of Chinese companies such as KingAgroot and Shandong Cynda actively promoting their discovery compounds and related formulations. However, the limitation of these companies is that they cannot afford the huge cost of global registration and channelization of their patent AIs. As a result, without multinational companies partnering with them, these innovative compounds are likely to be more limited to local applications in China and less likely to lead the growth of crop protection market value in the global market. It reminds me of the many patented compounds from Japanese companies that have missed the boat on entering the global crop protection market and ended up being replaced by iterations from multinationals. This is a very sad story.

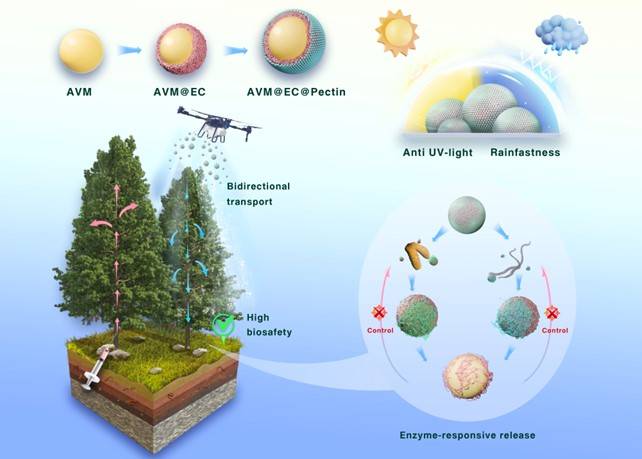

In the field of biologics, things can get relatively simple. For multinational companies seeking a competitive advantage, exploring biological active ingredients and forming products with outstanding capabilities is more attractive than the concept of biologics, such as biostimulants, itself. For example, the team of Prof. Xuemin Wu from the College of Science at China Agricultural University recently developed biomass-based, dual enzyme-responsive nanopesticides, for eco-friendly and efficient controlling of pine wood nematode disease.

The results were published in ACS NANO, a top journal in the field of materials science. The key of such research is the preparation of enzyme-responsive nanopesticides (AVM@EC@Pectin) using natural modified polymers as wall materials by micro-encapsulation.

When pine trees are infested by pine wood nematode and pine ink aspen, with the secretion and accumulation of cell wall degrading enzymes, the pesticide is released in intelligent response to cut off the infestation cycle of pine wood nematode and vector insects. It can realize the precise prevention and control of pine wood nematode disease.

In the field of microencapsulants, it is also a great challenge to control the accumulation of microplastics in the environment. This forces researchers to explore new innovative ideas based on existing raw materials and AIs. This is the reason why Prof. Wu Xuemin’s team can receive continuous attention from R&D teams of multinational companies.

Innovative Future: Cultivating the Ecology of Ag Innovation

If there is a future to be envisioned, what will be at the center of the future competitiveness of crop protection companies? It will be the first to establish an “Ecology of Ag Innovation.” The “Ecology of Ag Innovation” we are referring to is not independent of global agri-tech investments. It should be based on global agri-tech investments, and at same time, overlaid with China innovation and China supply chain (as shown in the figure below).

Any ecology needs soil to cultivate. The supply chain is the soil in which the “Ecology of Ag Innovation” grows. R&D and investments based on production and supply are sustainable and profitable. This is mainly because product brands and channels need to be supported by capital and sustainable production operations on the supply side. However, China’s supply side is currently facing significant challenges. This is not because China supply is in trouble. The main problem is that the potential for trade friction is rising.

At present, China’s supply, relying on a complete upstream industrial chain, occupies an absolute advantage in almost every field of industrial goods. Ricardo once asserted that if both countries have their own advantages in their respective fields, then trade will be beneficial to both sides. China’s supply now has an absolute advantage in terms of labor efficiency, the entire industrial chain, production costs and product quality. And this advantage covers almost all categories of capital goods. Although the low price of Chinese capital goods are the best way to reduce global inflation.

But this unique Chinese advantage is difficult for politicians in developed countries to accept. And China manufacturing is getting deeper into high value consumption goods. Therefore, in the context of global geopolitics, this Chinese supply advantage also sets the stage for more trade friction in the future. The European Union’s recent imposition of additional tariffs on Chinese-made electric cars is a clear example of this. Combined with the “de-Chinaization” and “China+1” strategies of some companies, this international situation is also stimulating Chinese companies to change their traditional B2B business model to a B2C market entry strategy.

As a result, the future of “Ecology of Ag Innovation” will not be confined to the borders of China.

The Ultimate Goal: Eco Goes to Overseas

As in the 1980s and 1990s, Japanese companies began to gradually emphasize overseas business. Japan shifted from a trade-based strategy established in the 1950s to an overseas investment-based strategy implemented after the Plaza Accord. As a result, Japan’s GDP reached total 542 trillion yen in 2021, and its net foreign assets was equivalent to 76% of GDP.

As with Japan’s predominantly local strategy of turning to overseas investment, Chinese pesticide companies should also actively seek the possibility of going overseas.

After China’s entry into the WTO, the capacity building of Chinese enterprises was set to meet global demand. Enterprises chose to build capacity generally 60% of the global demand to achieve lower production costs through the advantages of capacity scale. Nowadays, local enterprises are investing more and more in their own production capacity and category development, as each locality is actively promoting the growth of local enterprises.

As a result, competition in a free-market economy is becoming fierce. China’s complete upstream industrial chain and ample chemistry talents are also supporting factors. However, after facing competition for their products, companies inevitably choose to lower their prices in order to survive. At the same time, some enterprises that do not have the advantages of upstream raw materials and technology will be gradually eliminated. But this process may be longer.

The game between enterprises will always be carried out. In China’s pesticide market, this has created many short-term players. These companies expect to capitalize on the rapid registration of their products and get to market earlier than other China competitors in order to gain excessive returns. However, at a time when almost every company has the ability to register products quickly, the space for short-term, strategy-oriented players is gradually diminishing. Regardless, entrepreneurs will continue to invest in new categories and technologies. As a result, the competition is burning out from generic products to categories with expiring patent molecules.

As domestic competition intensifies and the potential for global trade friction rises, the question for Chinese enterprises, especially private ones, is where do the profits come from? The question for multinational corporations is how to sustainably globalize their strategic cooperation with Chinese suppliers?

The demographic dividend is probably the most cited Chinese advantage of the past few decades. Many people are concerned about the gradual fading of China’s demographic dividend. What they don’t understand is that China has already completed its shift from labor-intensive production to automated, continuous production. Due to its high level of education, China’s productivity per unit of labor is currently the biggest advantage of Chinese manufacturing. This labor productivity will be the cornerstone of China’s future sustainable development for a long time to come.

On the other hand, the future profitability of Chinese companies is largely dependent on resources. The key to sustainable and stable production is a sustainable supply of raw materials, like natural gas, crude oil, and downstream intermediates, regardless of where capacity is located. The third countries for “Eco Goes Overseas,” between China and the U.S., and between China and Europe, are the preferred locations for capacity spillovers. Target countries with relatively complete upstream raw material supply chains or relying on China’s raw material supply chains may be a good choice. At the same time, the target countries should be relatively stable in terms of national governance policies. This is conducive to a longer-term investment strategy for Chinese firms, as well as ensuring the sustainability of the returns of investment and promoting the sustainable development of the target country’s economy and employment.

Third, Chinese companies need the assistance of global capital. Investment in agricultural technology has shifted from a greater focus on the consumption of agricultural products to a focus on agricultural inputs. Investments in technology and R&D related to biologicals will become a hotspot again. This is mainly due to the need to take into account the future needs of the market at the time of investment. The demand for gene technology and biotechnology by MNCs will lead to a change in market demand.

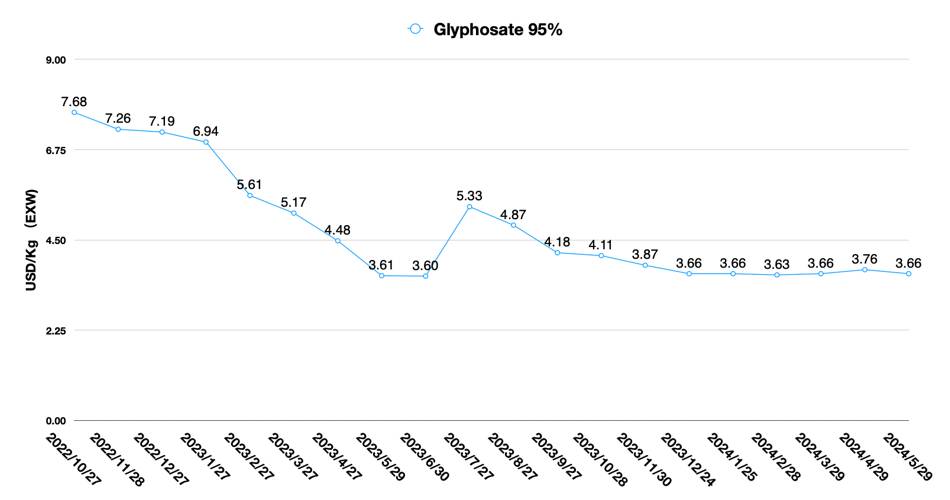

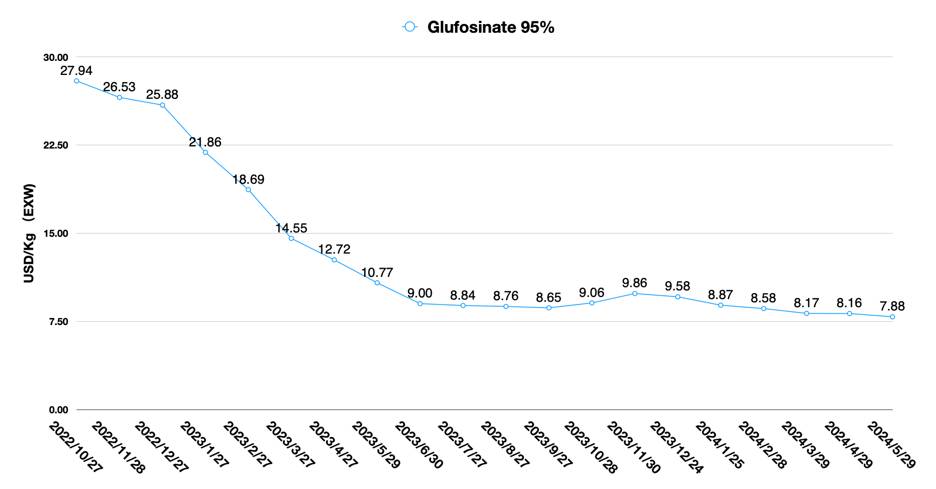

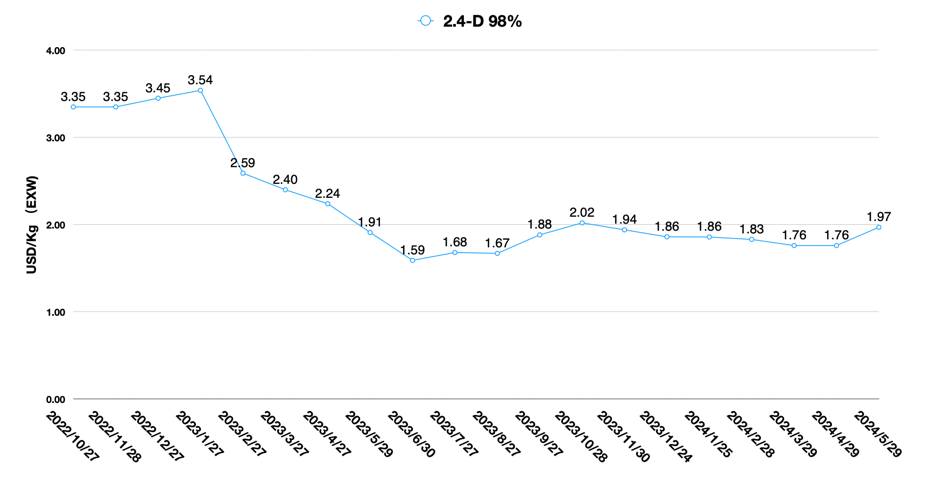

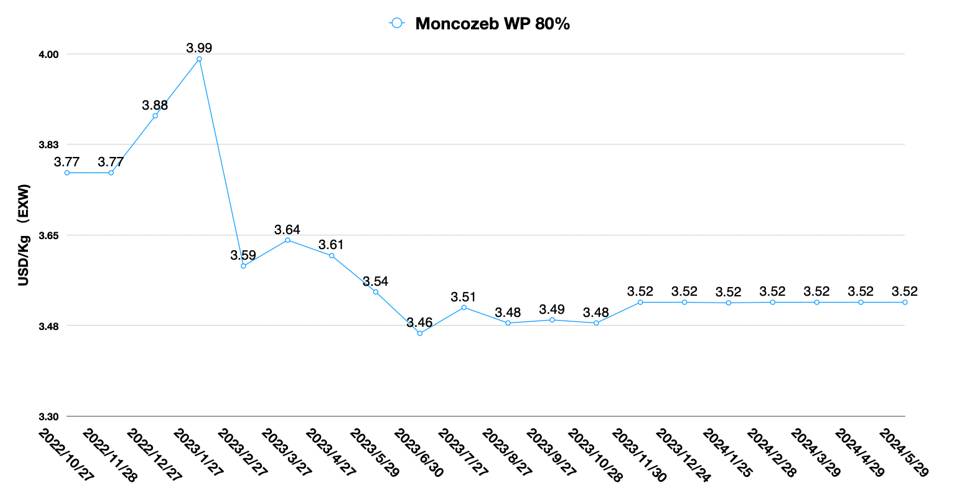

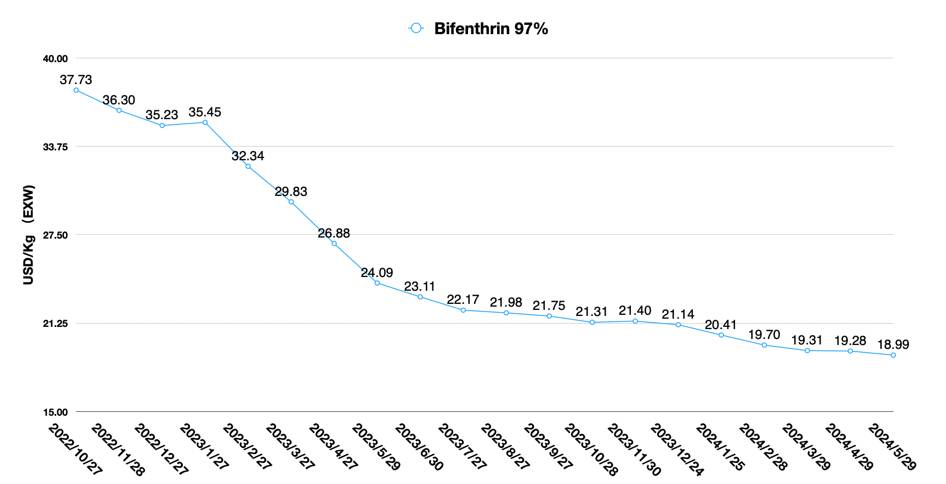

Fourthly, Chinese companies going overseas need to have in-depth strategic cooperation with more multinational companies. Currently, MNCs’ sourcing teams in China still focus on price and raw material costing as their main concerns. And Chinese sourcing teams mainly work on executing saving strategies rather than suggesting new cooperation strategies. This somehow fails to provide essential value to MNCs’ global management teams. As the price of AIs in China continues to run low, the costs borne by the MNC’s own production capacity are being greatly challenged. The Chinese sourcing team appears to be at a loss in this regard. Since MNCs stuff rarely have an entrepreneurial mindset, the primary function of the MNC’s China team remains that of a tool.

This may seem like a criticism, but it is a fact. Only when one is faced with the problem of survival will begin to think about how to keep the team alive, and what external conditions the team needs in order to achieve its survival goals. Silver spoon resumes can only help mature companies to manage, but it can’t help companies to break out of the predicament.

The global teams of multinational companies need to undergo a profound cognitive shift from gaming Chinese suppliers to globalized strategic cooperation. The performance of MNCs is generally affected by sluggish demand and de-stocking in the global crop protection market. As a result, it is difficult for MNCs to consolidate resources internally for strategic investments. Financial pressures are also a contributing factor.

Therefore, the focus today should shift to how to obtain external support from Chinese companies and global venture capital. Establishing an “Ecology of Ag Innovation” centered on MNC channels may become another growth pole for MNCs and global ag input distribution companies in the future.

At the very least, multinationals still have an advantage in detecting growth margins in the market. Chinese suppliers, on the other hand, still have the primary sales objective of supplying multinationals. Inherent strategic complementarities could compensate for the negative impact of trade frictions and geopolitics on global performance growth.

S.W.A.T.

Each company will have its own special idea about the future “Ecology of Ag Innovation” operation model. Due to the fact that we work a lot with multinational companies, we believe that in the future multinational companies will need more S.W.A.T. like teams. Such special teams should be above all existing departments and have the ability to mobilize resources from all departments. They should be interspersed across organizational structures and regional subsidiaries, liaising closely with investors and Chinese suppliers as well as third-country government, developing strategies and executing them with conviction. More importantly, they report directly to the CEO, and their role is to establish and maintain the company’s unique “Ecology of Ag Innovation” operation, which facilitates the company’s identification and refocusing of new growth frontiers.